This is the first week of Collaborative Unit.We held an online meeting on Monday by Skype with our collaborator Stephen,the director of an organization called r0g,whcih is a Berlin-based non-profit agency for open culture and critical transformation.

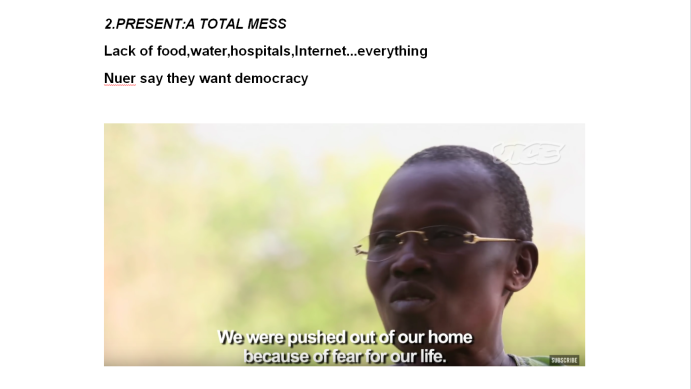

Stephen told us a lot about the history of the civil war in South Sudan,including a lot of names( the name of president :Salva Kiir Mayardit,the name of vice president:DR. Rick Macher Teng and two tribes :Dinka and Nuer).It sounded really complicated about kind of historic stuff.Stephen gave us not a very clear brief for this project.He mentioned that plenty of diasporas (South Sudanese living outside South Sudan) post some fake or exaggerated news or pictures on social media,which actually help to stimulate conflicts in South Sudan.Most people living in South Sudan do not have access to Internet and the posts spread from mouth to mouth from people who views them on social media.Stephen wanted us to find some connections on social media and provide him with some useful information,which seemed like super tricky.

There were too much information and I really needed time to digest and understand.Therefore,I search for more information about the history and conflicts in South Sudan online to help me get a picture of this tricky brief.

Video 1

Online hate speech and incitement is on the rise in South Sudan

Social media users are increasingly facing threats after posting online.

Video 2

Saving South Sudan – Full Length

Murder,rape,other atrocities everywhere and massive starvation

Passage 1

How to use facebook and fake news to get people to murder each other

1.Adult literacy rate:30% , lack of the access to Internet

2.Social media incitement mainly posted by the South Sudanese diaspora

3.ways of incitement:

“Social media has been used by partisans on all sides, including some senior government officials, to exaggerate incidents, spread falsehoods and veiled threats or post outright messages of incitement”

- The groups are based abroad, are believed to be for-profit, prey on a general lack of media literacy, and specialize in setting up confusingly named websites to share false news and unverified images.

- How this works:

People read these messages and react on the ground

“They can post an inciting message: ‘You of x tribe, what are you waiting for? Such tribe are finishing us, let us go and revenge!’” said James Bidal, an activist with South Sudanese civil society group Community Empowerment for Progress Organization, which monitors online hate speech. “People read these messages and react on the ground.”

The few people online quickly share it by word of mouth with the offline Community

According to Bidal, when a trusted diaspora “influencer” posts a comment on social media, the few people online in South Sudan who see it may quickly share it by word of mouth with the offline community. “They take the message very seriously and they keep spreading,” he said.

- Researchers say diaspora influencers work together in well coordinated and funded campaigns to spread false news and vitriol, coalescing around a single message.

“You could imagine a scenario where somebody working on this hate campaign may be sitting in North America and has a partner or a colleague in Australia or New Zealand, and are kind of working around the clock,” Kovats said. “You can have a 24-hour, moving campaign.”

7.A common tactic is to post images and videos from other African conflicts — pictures of bodies from the Rwanda genocide, for instance — while claiming they depict the massacre of a particular South Sudanese tribe.

- In some cases, the images are stamped with logos of known international news organizations — their creators are especially fond of the Associated Press’s distinctive logo — in an attempt to lend legitimacy.

- “Hoax messaging, fear propaganda — that’s a really simple way of creating hysteria and fear by people who justdon’t know how to interpret these kinds of images and where they come from,” said Kovats of #DefyHateNow.

- The UN experts panel said in their November report thata senior government military officer showed them an unverified cell phone video as proof that rebels committed an atrocity. Machar’s spokesman James Gatdet likewise once claimed on Facebook that Kiir’s guards tried to arrest the rebel leader, sparking condemnation from the South Sudanese government, which forced him to take down the post.

Passage 2

THE LOST HOPES FOR SOUTH SUDAN

- On December 15, 2013, Kiir,fearing a coup, ordered Dinka members of his Presidential Guard to disarm their Nuer counterparts. The coup plot was almost certainly a false alarm, but Kiir’s soldiers nevertheless went house to house, killing thousands of defenseless Nuer men, women, and children. Those who tried to escape were herded into grass-thatched houses that were doused with kerosene and set alight. Some were forced to drink each other’s blood. A rebel movement allied to Machar reacted by mowing down thousands of others, mostly Dinka, decapitating some of the bodies. Women and children had their limbs cut off and were raped with various objects.

- For the next two years, thousands of Ugandan troops propped up Kiir and fought Machar. Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni had long seen Kiir as a protégé and Machar as a rival.

- Finally, in August, 2015, the two factions in South Sudan signed a peace deal. Under its terms, the capital city of Juba would be demilitarized, Kiir’s troops would be confined to their barracks, and Machar would serve as Kiir’s Vice-President once again.

- Everyone knew that asking the two men to share power was a risky proposition. They hated each other. Nevertheless, both had strong, well-armed followings, and, since both refused to step down, a detente based on a balance of military power seemed the only way to secure a ceasefire. But, as the months wore on, Kiirfailed to hold up his side of the bargain. His troops were not demobilized, and Machar, fearing for his life if he returned to Juba, stayed away. Under intense international pressure, especially from the U.S., Machar finally returned to Juba in April, 2016. As he had feared, he was entering a trap. On July 8th, as Machar and Kiir were meeting at the Presidential Palace, Kiir’s troops attacked Machar’s bodyguards. At least three hundred people, including civilians, were killed in the ensuing mayhem. Troops marauding through the city also raped aid workers and murdered foreign peacekeepers and refugees who were sheltering in a U.N. compound. Machar, under intense ground attacks and aerial bombardment, sustained severe injuries and spent forty days in flight through the forests of Congo.

- Anyone suspected of loyaltyto Machar is in severe danger; many innocent men, women, and children are again being massacred.

- Even more important than the responsibility to protect is the responsibility to prevent, using negotiation, diplomacy, and sanctions long before the killing starts. By then, it is far, far too late.

Passage 3

Atrocity photos – fake and real – increasingly used by S Sudanese propagandists

- taken from other contexts and are deliberately used to fan ethnic hatred

- Other images circulated among South Sudanese online recently may be authentic, showing actual South Sudanese victims, but are posted without any description as to where the photographs were taken, when, or by whom. This makes it difficult to determine whether a photograph is legitimate versus when it has been appropriated from another context.

- South Sudanese diaspora sometimes play a critical role in circulating such false information and propaganda. In this case, the photo was uploaded to Facebook by Adol Ijong, a South Sudanese living in Rochester, Minnesota, USA, and shared by others. Adol provided no explanation as to why she had used the non-South Sudanese atrocity photograph and wrongly implied it was an image from South Sudan.

- The lack of detail or context provided in relation to purported atrocity photos means that they are easily misappropriated even when they do appear to be authentic.

- Facebook users also implicitly call for acts of revenge and violence when sharing atrocity photos.

- A Facebook user in the diaspora, Daniella Valentino wrote, “Are the pictures of dead people that I am seeing online from RSS [Republic of South Sudan]? Who took them and why that person was left alive by killers? What do people want to achieve from showing those pictures and do they have permission from victims families? I need to know are pictures from RSS??”

Conclusion

Now I am more clear about what is happening in South Sudan and actually feel sad and terrible for people suffering from war.I start to find this project meaningful for the impact of design in the real world.To be honest,I have no idea about what to do after gathering these background knowledge but I will do research on some influencers on Facebook and try to find something useful.